We currently find ourselves in a very volatile market driven by fear and uncertainty courtesy of the expansive tariff policy being enacted by the Trump administration. As I write this article, the S&P 500 is down 4% in a single day, which represents the largest one-day selloff since 2022. This volatility encapsulates the fear generated by these policies. I am not going to sugar coat it: tariffs are bad policy that will detract from US and global growth in addition to likely resulting in higher prices for consumers. However, the fear and market volatility associated with these tariffs appears to be overblown. Of course, there are negative and unseen risks, but the market appears to be pricing in a full-blown recession, which seems a bit hasty in my view. That being said, policies like this are going to hit certain people, families, and businesses very hard, and my thoughts go out to these folks. With that said, in my analysis, a full-blown recession and bear market caused by these tariffs appears to be unlikely.

To understand what the true effect of these tariff policies may be, we need to understand what tariffs are, what they are not, and the logistics of the implementation of tariffs in the real world.

What is a Tariff

Put simply, a tariff is a tax on imported goods. Tariffs have been used frequently throughout history with the first recorded tariff in the United States being put in place by George Washington on July 4th, 1789.[i] Tariffs have been viewed as having a dual purpose: to raise tax revenue to fund the government and to protect domestic businesses from foreign competition. As a tool for generating tax revenue, the United States has slowly veered away from this methodology since the introduction of the income tax in 1913. In the end, a tariff is just another form of taxation.[ii] As for “protecting” domestic businesses from foreign competition, it is debatable in my view whether tariffs protect domestic businesses in any meaningful way. I will go into the effects of tariffs later in this article.

The Logistics of Tariffs

The current narrative coming from the Trump administration is that a tariff is a “tax” on the exporting country. There is some truth to this, but it is much more complicated than what is currently being “sold” to the American public. In a hypothetical world, the importing company is the one on the hook to pay the tariff when it brings the goods into the country.

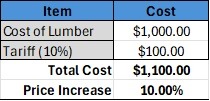

Let’s say Company A imports lumber from Company B, which is in another country. If the cost of this lumber is $1,000 and a 10% tariff is in place, Company A will pay Company B $1,000 for the lumber. From there, Company B will ship the lumber to Company A through a port of entry. For the lumber to clear customs at the port, Company A will need to pay the 10% tariff ($100 in this case) to Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) before it can take possession of the lumber, see Exhibit 1 below. In this hypothetical world, the importer is on the hook for the tariff and likely passes the cost on to consumers or eats the cost (or some portion of the cost) themselves.[iii]

Exhibit 1: Simplified Tariff Analysis

How Tariffs Work in the Real World

As mentioned previously, in a hypothetical world, the importer pays the tariff to take control of the imported goods. Even in practical application, the tariff itself still must be paid by the importer, but the actual logistics of pricing and importing can vary greatly in the real world.

Let’s look at the above example, but in a real-world situation.

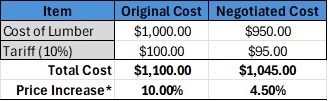

A 10% tariff on lumber gets put in place. Company A calls up Company B and says something like “this tariff is too high of a cost for me to bear on my own and I would like to negotiate the price with you, or I will find another company who will negotiate.” This is how business is done in the real world. Company A and Company B will then negotiate the price to help offset the cost of the tariff. Perhaps they will decide to split the cost and Company B will reduce the price by 5% to $950. At that point, Company A would purchase the lumber, then pay the 10% tariff to take possession of the lumber for a total price of $1,045. This would result in a total cost increase of 4.5% resulting from the 10% tariff, see Exhibit 2 below. This is the most basic version of how tariffs get “priced” into products.

Exhibit 2: Tariffs and Price Negotiations

In a more complex situation, Company B may negotiate selling the lumber to Company A through a middleman who is domiciled in a country with a more favorable tariff rate. Perhaps Company B would even create a partnership with a business in Company A’s country that gets preferred treatment or has some sort of reciprocal benefit that could reduce the impact of the tariffs even further. Over time, good business people and smart business practice help mitigate the economic effect of tariffs significantly and we live in a very globally sophisticated world.

The Currency Effect

Taking the effect and costs of tariffs one level further, we also need to consider currency fluctuations. Currency valuation is very complex. As a result, we will only be looking at tariffs in isolation for this example. There are thousands of variables that play into the value of currency, but ultimately the value is driven by supply and demand.

A tariff reduces the demand for the exporter’s currency, which contributes to its devaluation as it pertains to the importer’s currency. Every time a good or service is imported it is effectively a “sale” of the importers currency and a “purchase” of the exporters currency. In general, a tariff tends to reduce overall imports from the tariffed country, which means that less dollars are being exchanged for the exporter’s currency. Less dollars being sold in order to buy the exporters’ currency means the exporters’ currency will devalue relative to the US Dollar (USD).

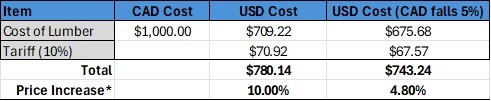

Let’s go back to the lumber example and, in this case, assume the exporter is from Canada and using the Canadian Dollar (CAD).

In this scenario, the lumber is still priced at $1,000, but now that value is in CAD. If the effect of the implemented tariff was a 5% decrease in the value of the CAD relatively to the USD, then the US importer can buy the goods from the Canadian exporter for 5% less, offsetting a large percentage of the implemented tariff. Let’s break this down using real exchange rates.

As of April 3, 2025, $1 USD buys approximately CAD$1.41[iv]. Which means, to buy CAD$1,000 worth of lumber would cost the importer $709.22 USD ($1000 / 1.41 = $709.22) and a 10% tariff would increase the total cost to $780.14 USD ($709.22 x 110% = $780.14). If the CAD fell 5% in value to CAD$1.48 per $1 USD, then that same amount of lumber could be purchased for $675.68 USD ($1000 / 1.48 = $675.68) and, after the 10% tariff, the total cost would be $743.24 USD ($675.68 x 110% = $743.24). The total cost would only be 4.8% higher in USD than it was without the tariff ((743.24 – 709.22) / 709.22 = .048 or 4.8%), see Exhibit 3 below.

Exhibit 3

Ultimately, tariffs are bad policy and only make things more expensive and less efficient, like every other tax does. However, the actual effects of implemented tariffs are far less than they may appear to be at face value. As shown in the above examples, a 10% tariff will not result in a 10% increase in price or a corresponding reduction in GDP. The price increases and GDP effects will be mitigated significantly if not side-stepped altogether.

The Trump Tariff Policy (as it stands today)

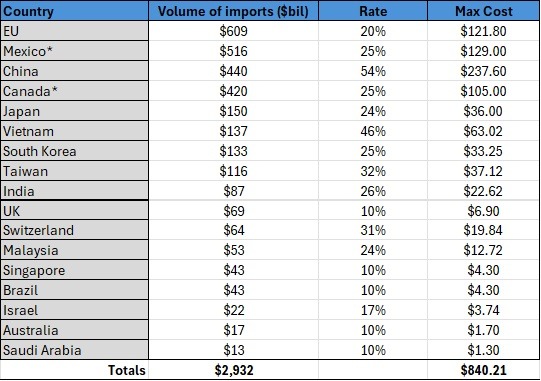

Now that we have a good understanding of tariffs, how they are implemented, and their economic effects, we can analyze what we are seeing from the Trump administration. See Exhibit 4 below for a breakdown of the current proposed tariffs.

Exhibit 4: Current Tariff Proposals

As you can see from Exhibit 4 above, there are a myriad of proposed tariffs, some of which have already been implemented. These numbers are large and numerous, but what does it all mean? The media would have us believe that a tariff is a dollar-for-dollar reduction of US GDP and an increase in cost to the consumer, which would be devastating and likely put the US into a recession. However, I think we have thoroughly debunked that in our above exploration of the real-world implications of tariffs, but let’s run through the numbers anyway.

The total estimated cost of the tariffs in Exhibit 4 is $840.21 billion dollars. 2024 US GDP was approximately $29.723 trillion, which means the cost of these tariffs would equate to about 2.83% of GDP, or approximately the equivalent amount to GDP growth estimates.[v] So, if this were a dollar-for-dollar reduction in GDP, US growth would be flat or slightly negative going forward because of these tariffs. Although the actual effect is difficult to predict, as it stands today, the effect of these tariffs will be far less than the face value and have a very low likelihood of putting the US into a recession.

From a global perspective, these numbers are really a drop in the bucket. Global GDP in 2024 was approximately $110.06 trillion, which means the face value of these tariffs would be approximately 0.76%.[vi] Again, it is not good, but not anywhere near large enough to put the world into a recession. The tariffs will create headwinds, especially in the US, but are just not large enough a factor in the sophisticated global market we have today to cause a global recession.

The Trump Effect

One of the major fears among investors is the unpredictability of President Trump, and this is indeed a legitimate fear. The man is hard to predict. However, we can learn from his past policy decisions to understand how he tends to operate. In general, Trump views himself as the world’s best “deal maker”, which means he comes out strong and hard in the beginning and then backs off in the face of a compromise. We have seen this time and time again. Even recently, with the Mexico and Canada tariffs, he ended up exempting all of the USMCA-covered goods without getting any concessions from either nation. If he does get concessions of any kind, he will likely be quick to reduce or get rid of the tariffs. While nothing is guaranteed with our current president, our view is that this is “peak” policy, which will likely get watered down as negotiations begin to take place.

What This Means for Investors

When it comes to capital markets, widely known information gets priced in very quickly so things that we hear about on the news are already reflected in the current prices. Since markets are very efficient, making portfolio changes based on news stories is an exercise in futility. When markets are down and people are in panic mode, it is the worst time to make rash portfolio decisions like running for cover and going to cash. Your fears are already priced in, and you are likely locking in your losses. Statistically, the further markets fall, the more likely growth will be over the mid and longer term. Now, the current tariff policies are creating additional headwinds here in the United States, which already had some inefficiencies in the markets with high valuations and stocks priced to perfection. This may create some additional opportunity in foreign markets. Thus, individuals with globally diversified portfolios are likely doing much better than their US-only counterparts.

Our advice is that, if you have a well-diversified, purpose-built portfolio, now is the time to stay disciplined and grit your teeth until we get to the other end of this correction. If you have a narrow portfolio, now could be the time to consider international diversification like we do for all our clients.

Additional Risks to Consider

Given the efficiency of pricing in news, it is not what the media is discussing that you need to pay attention to. In this case, the effect of tariffs is already priced in. What is not likely to be priced in is the potential effect of reduced capital investment caused by uncertainty, particularly here in the US. The lack of policy consistency could cause businesses to halt investment, which is one of the primary drivers of economic growth. This has not happened yet, and takes many months to happen, but if it does come to pass, it could be the catalyst for a recession. Second, there is a risk of a true global trade war breaking out. What we are seeing now with “retaliatory tariffs” is small and not very meaningful, but if the rest of the world starts implementing sweeping tariffs, quotas, and embargos, then a recession will become more likely. While world leaders would have to be incredibly stupid to put their citizens in this situation, I’ve never thought politicians were the sharpest knives in the drawer.

Keep a watchful eye, stay unemotional, be objective, and make sure your will is made of iron. We do not know how long this correction will last or how deep it might go, but when it reverses, it will be hard and fast.

If you have questions or are interested in getting a second opinion on your portfolio, please do not hesitate to reach out to us. We are always happy to chat.

[i] https://www.history.com/articles/what-is-a-tariff

[ii] https://www.investopedia.com/articles/tax/10/history-taxes.asp

[iii] https://www.trade.gov/import-tariffs-fees-overview-and-resources

[iv] https://finance.yahoo.com/quote/CAD%3DX/

[v] https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/GDP

[vi] https://statisticstimes.com/economy/world-gdp.php

This content is developed from sources believed to be providing accurate information but Delphi Advisers, LLC does not warrant that this information will be free from error. This information should not be considered legal, tax, or financial advice. Please consult legal or tax professionals for specific information regarding your individual situation. The opinions expressed and material provided are for general information, and should not be considered a solicitation for the purchase or sale of any security, investment, tax, or legal advice. Delphi Advisers, LLC is registered as an investment adviser in the state of Washington and is licensed to do business in any state where registered or otherwise exempt from registration